Concept: Education

- Functions

- Education

Details

Generations of Solomon Islanders have taught their children by example, whether in agriculture, fishing, fighting, or the intricacies of behaviour, custom, ancestor worship or gender categories. While urban life has modified traditional education, in many rural areas education continues much as before. In the past, people had complex systems of counting and ways for passing messages. Learning began at birth in the safety, security and intimacy of the immediate family. Early on, children realised that they were part of an extended family and that there were no divisions between parents and siblings and the wider family circle. Hamlets and villages were usually close together and children soon began to wander between them, conscious of belonging to a wider group, aware of relationships with the living and ancestors all around. Coastal children were and are at home in the water, and learn to use canoes at a remarkably young age. Education still includes learning proper behaviours, mutual help, maintaining harmony and avoiding inappropriate displays of anger. Learning is gendered with quite clear male and female roles. Beyond the hamlet, village or island are strangers, enemies and sorcery, to be negotiated with care.

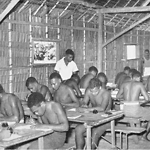

However, the Protectorate years required a new set of skills in writing and mathematics. Early literacy began overseas when Solomon Islanders learnt to read and write in mission schools in Queensland and Fiji that were based on delivering the Christian message. Thousands of labourers returned minimally literate; occasionally they had been educated in government primary schools, such as was Timothy George Maharatta (q.v.) from Malaita, who attended such a school in Queensland. Within the Solomons, the early Christian missions continued much the same type of education as on the foreign plantations, based on the Bible and learning practical skills. The Anglican Melanesian Mission schools were the longest established, although their standards were quite low. The Kohimarama model was used (from the Mission's initial school of that name at Auckland), in which students studied and worked in school gardens. The best early mission education systems were run by the Methodists, the Anglicans and the Seventh-day Adventists.

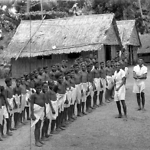

In the early years, the largest numbers of Solomon Islanders who received a rudimentary Western education attended the Melanesian Mission's Norfolk Island School, established in 1867. There were four boarding houses, a dining hall, chapel and hospital, plus gardens. In a six-year course students were taught reading, writing, arithmetic, singing, farming, carpentry, and, of course, Christianity. They were recruited in the islands and taken back to Norfolk Island, then returned home after two years, before returning to Norfolk again. The focus was on young males, although wives were included in the later years of a student's time at the school.

In 1893, the Melanesian Mission (q.v.) purchased land at Siota in Mboli Passage, Nggela, and a school was erected there in 1896. Unfortunately, an 1897 dysentery outbreak killed eleven of the forty-seven students, and the school site was closed in 1900 as unhealthy. (Boutilier 1974, 39) In 1910, the Melanesian Mission tried again with a new school at Bungana Island, also in the Nggela Islands, which enrolled eighteen students from Makira, Guadalcanal and Isabel. The next year they established St. Michael's, a boarding school for boys at Pamua on Makira, which eventually became the Protectorate's best-known school. Five years later, the Melanesian Mission established St. Mary's Theological College (q.v.) at Marovovo at the northwestern end of Guadalcanal. In 1922, St. Mary's became the junior school for the Melanesian Mission. That same year All Hallows (q.v.), the Mission's senior school, was established at Pawa on Ugi Island. It was intended to fill the gap created when St. Barnabas' School on Norfolk Island closed in 1919. The first Anglican boarding school for girls began at Boromole on Nggela in 1917 and then moved to Siota in 1918 and to Bungana in 1920. A college dedicated to training for the deaconate began at Naka on Malaita in 1933 and moved the Taroaniara on Nggela in 1939. The Melanesian Mission also operated many village schools, run by teachers or catechists. In 1925, 290 students were attending five Melanesian Mission schools run by Europeans. Two were elementary, one elementary and industrial, one secondary and one advanced. The subjects taught were reading, writing, and arithmetic and religious knowledge. (AR 1924-1925, 9; Boutilier 1974, 52-54)

In 1902, the Methodist (q.v.) began their mission in the Western Solomons, following an industrial education model, which included plantations combined with institutions to impart technical and industrial skills and Christianity. Methodist converts participated in carpentry, boatbuilding, saw-milling and plantation work. By 1930, the Methodists had established 105 primary schools with an enrolment of 2,642. The main centres were Bilua on Vella Lavella, at Patutiva near Seghe in Marovo Lagoon, and at Kokeqolo in Roviana Lagoon. There was also a day school with 211 students and a secondary college with thirty-three students at Kokeqolo, the Mission's headquarters. The college provided technical education and trained pastors and teachers with considerable success. Village schoolteachers had only basic educations and classes seldom lasted for more than two hours a day, fitted in with other local routines. (Boutilier 1974, 40-41)

The Catholics (q.v.), although their Mission had been permanently established in the Protectorate since the 1890s, had limited interest in imparting education other than religious instruction. However, in 1899 thirty-five students were being taught at Rua Sura Mission, on an island off northeast Guadalcanal, and another Catholic station also began at Avuavu on Guadalcanal's Weathercoast. Sister Mary Leon is credited with establishing the first girls' school at Visale (q.v.), Guadalcanal. The Gari language of the Tangarare area was used for education on Guadalcanal. (Pollard and Waring 2010, 12) In 1925, the Marist missionaries had 282 girls and 444 boys attending their boarding schools, their principal purpose being religious and moral training, which was accompanied by reading, writing, arithmetic and singing. There was no formal industrial education, although students assisted with boatbuilding, concrete work and printing, learning on the job. (AR 1924-1925, 8, AR 1925-1926, 8)

In 1928, the Catholics established boarding schools for boys and girls at Wainoni Bay, Makira, at Mbuma in Langalanga Lagoon and at Rohinari in the 'Are'are area, the latter two both on Malaita. Wanoni School became a plantation where students made copra following a model of industry-based education then widely accepted. In 1936, a senior training institute began at Marau Sound, Guadalcanal, which also used preparation for work and village work as part of its rationale. Three years later it was judged to be the most successful school in the Protectorate. Catholic village-level schools were of low quality, however, as there was no defined syllabus and teaching was poor. (Boutilier 1974, 43-44)

Men who attended mission schools in Queensland and Fiji-mainly of the Anglican, Presbyterian and QKM missions-returned to the Solomons beginning in the early 1890s, but primarily from the late 1890s into the 1900s. Some of these Queensland and Fiji converts started Christian colonies and established schools around Malaita and Guadalcanal and other islands. These schools were meant primarily to impart Christianity but also taught low-level literacy if the teacher was capable. Dozens of these 'Bible schools' formed the foundation of literacy in the Protectorate. The earliest Queensland Kanaka Mission (q.v.) ones in the Solomons were probably those started by Samson Jacko at Malageti on the south coast of Guadalcanal in 1892, by Peter Abu'ofa (q.v.) at Malu'u in north Malaita in 1895, and David Sango at Talise on Guadalcanal in the early 1900s. (Boutilier 1974, 46)

The South Sea Evangelical Mission (SSEM) (q.v.) was founded as the Queensland Kanaka Mission (QKM) in Bundaberg, Australia, in 1886, and transferred to the Solomon Islands between 1895 and 1907. The SSEM, like other Christian denominations, provided literacy classes to teach students to read and write the Bible and sing hymns. Onepusu, just south of Langalanga Lagoon on Malaita, was chosen as the SSEM headquarters and a small boarding school for boys and girls was established there in 1906. In 1911, the SSEM began another school at Wanoni Bay, Makira, on the site of one founded by another returned labourer. Along with the Methodists, the SSEM believed in industrial training and from 1909 the founder Florence Young convinced her brothers, who were sugar plantation owners in Queensland, to open a large copra plantation centred at Baunani on Malaita's west coast, not far from Onepusu. The Malayta Company included evening education in its activities, just as the Youngs had done in Queensland in their QKM, and the SSEM transferred its boys' training school to Baunani in 1911, where it remained until the company shifted its focus to the Russell Islands in 1918. (Boutilier 1974, 47-48; Pollard and Waring 2010, 12)

The Onepusu School had a senior and junior section, based not on age but rather the length of prior schooling. The seniors, about one-third of the enrolment, remained for three to four years, while the juniors stayed for one to two years. The main purpose of the SSEM schools was religious, training youths to spread Christianity. Standards were low and when the Malaita District Officer visited in 1930 he reported that only a few of the senior students could complete elementary sums in arithmetic and none understood fractions. Junior students were taught to read and write, and some extra practical instruction was given in carpentry and plumbing. The SSEM had numerous other Bible Schools on Malaita, which taught literacy entwined with religious instruction. In 1925, the SSEM had two schools with European teachers in charge and 160 students. The schools taught composition, spelling, arithmetic, singing, religion, carpentry and boatbuilding, and canoe and cabinet making. Schools taught by indigenous teachers were attended by 7,542 students who learned reading in English and local languages and singing. (AR 1924-1925, 9; Boutilier 1974, 48-50)

The Seventh-day Adventists (q.v.) began work in the Solomon Islands in 1914, when they established a mission station at Gizo (q.v.), and soon after they began district boarding schools. In 1925, forty-six Seventh-day Adventist schools were attended by 351 girls and 527 boys. The curriculum consisted of Bible studies, reading in English and local languages, English spelling and conversation, arithmetic, writing and singing. A limited number of students were also instructed in typing, typesetting and printing and carpentry. (AR 1924-1925, 8) By 1930, the Adventists had seven village schools around Marovo Lagoon, with their headquarters at Batuna, a boys' boarding school at Nafinua on Kwai Island off Malaita's east coast, and a school and medical centre at Kwailabesi on Malaita's northwest coast. There was a district headquarters school at Kopiu, near Marau Sound on Guadalcanal, and they were also active on the south coast of that island. Like the SSEMs, the Adventists were fundamentalist Christians who believed in an imminent second coming, but they also invested a lot of energy into education and health. A similar application came from chiefs Selwyn Aloa and Patrick Kike in Nggela, who wanted to pay for two of their boys to be educated in Fiji for four years, to return as advisors to the chiefs. Neither request was granted, but the government was aware of its responsibilities and considered applying to the Colonial Development Fund for money to subsidise mission schools, as long as they included some standard subjects in their curriculum. But because the missions were unwilling to forego their autonomy, nothing happened. (Bennett 1987, 258-259; Boutilier 1974, 56)

In 1922, there were 3,271 students recorded as attending schools in the Protectorate: 353 at Adventist schools, 630 at Catholic schools, 120 at SSEM schools, 2,178 at Melanesian Mission schools, and an unknown number at Methodist schools. (Boutilier 1974, 75) Starting in 1926-1927 the administration provided grants to foster mission education programmes, with an emphasis on technical education, and the next year it was announced that Solomon Islander students would be sent for training at the Fiji Medical School. Particularly after William Bell (q.v.) was killed on Malaita in 1927, the administration realised that without modern education little progress could be expected. By the 1920s and 1930s, there was also a will to begin to involve Solomon Islanders in the lower levels of the public service and in the commercial companies, which would require a concerted effort to raise the level of education. The answer seemed to be to create a central government school. When the Head Tax was imposed in the early 1920s, the administration granted exemptions to 'scholars attending schools presided over by European teachers' and for 'native preachers who conduct daily schools', as a means of encouraging education. This was disallowed in 1930 and instead a subsidy was granted to missions which provided secular education. The missions were outraged and refused their support, which forced the Protectorate to give £100 grants to each of the main mission training schools. In 1930-1931, there were 8,555 registered students: 1,020 at Adventist schools, 792 at Catholic schools, 116 at SSEM schools, 3,904 at Melanesian Mission schools, and 2,723 at Methodist schools. (Boutilier 1974, 75) Hugh Laracy (1976, 90) notes that by the 1930s the best-educated Solomon Islanders were probably Methodist since they were the main indigenous clerks in the government service. In 1934, the Resident Commissioner met with mission representatives and decided to refer the matter of grants to the missions to the Colonial Office. This led to a full-scale survey of education in the Protectorate in 1939, conducted by William C. Groves, who was seconded from the Victorian Government in Australia. His final report was completed in 1940, but there was no money to introduce his recommendations and by 1942 the Solomons was embroiled in the Second World War. At the time of Groves' report, there were only 4,748 students, clearly showing the impact of the economic depression: 910 attended Adventist schools, 777 Catholic schools, 280 SSEM boarding schools, 539 Melanesian Mission schools, and 2,238 Methodist schools. Surprisingly, between 1922 and 1939 girls made up around 60 percent of the students. (Boutilier 1974, 56-64, 75)

A Protectorate Education Department was established in 1946 with three positions, but it functioned under considerable difficulties. Director C. A. Colman-Porter resigned in 1948 and was not replaced until January 1950, which left an inspector of mission schools as the only person in the Department during 1949, and she departed in 1950. Missions continued to conduct all education in the Protectorate, except for a part-time school in Honiara for European children, and the Chung Wah School (q.v.) for Chinese children which opened in October 1949. The Auki Experimental Primary School (q.v.) opened in 1947 but floundered until an adequate Headmaster was appointed in April 1950. He resigned a month later, unhappy with funding and conditions, which left the acting Director (in Honiara) to act as Headmaster as well. The Honiara Woodford School for European children was housed in the British Red Cross Society's building and the students were enrolled in the New Zealand Correspondence School. Because student numbers were increasing, in July 1954 the government decided to convert an existing building into a school and to follow a normal curriculum conducted by a trained teacher. Outstation European children received financial assistance to take correspondence courses from New Zealand or Australia. (AR 1953-1954, 26)

The postwar BSIP government initiatives flowed from the appointment of Colman-Porter and his November 1947 conference for all educators, and a new policy outline to create state institution to impart skills for the Protectorate in teaching, nursing, agriculture, commerce, carpentry and engineering. The only concession to the missions was a plan to allow colleges within these institutions that were organised according to religious denominations. This development was delayed after Coleman-Porter resigned when he realised that he did not have the support of the government. A new conference was held in March 1949, organised by Howard Hayden, Education Adviser to the WPHC, which was no more conciliatory to the churches than the 1947 conference had been. New BSIP education regulations were circulated in 1953 that stipulated new multi-course colleges to produce practitioners in all of the skills needed to develop the Protectorate. (Laracy 1976, 151-152) This was the foundation of what eventually became the Teacher and Vocational Training College, the British Solomon Islands Training College (q.v.), the Agricultural Staff Training Institute (q.v.), Central Hospital in Honiara Dressers' School, the Nurses' Training Centre (q.v.), Auki Boatbuilding School (q.v. Auki), the T. S. Ranadi Marine Training School (q.v.), and finally the Solomon Islands College of Higher Education (q.v.).

With no co-ordinating legislation, each mission had been able to pursue its own curriculum. The Auki Experimental School was a forerunner of plans for wider government participation in the education system. The school closed for a while and reopened in 1952, staffed by one female teacher, with the intention of training boys to enter teacher-training institutions and the public service. The next government school was built at Aligegeo village, five kilometres inland from Auki; the forerunner of what became King George VI boarding school (q.v.) in September 1952. (Kenilorea 2008, 47-48; AR 1953-1954, 26) In 1959, 'KGVI', as it is affectionately known today, was extended to include secondary education, and it was planned for it to become solely a secondary school. In 1966, the school was moved to Honiara and the next year it became fully co-educational. In its early years, the school was a remarkable hothouse for producing a new Solomon Islands elite, with students such as Peter Kenilorea and Solomon Mamaloni. (Kenilorea 2008, 47-93)

By the end of 1952 the Education Department had established five elementary schools on Malaita. Although there were early twentieth-century attempts to educate girls, the major efforts were initiated in the late 1940s by the SSEM, the Catholics and the Anglicans. Catholics established the Villa Maria Teacher' Training School at Visale, and girls' schools at Visale and Tangare. The Anglicans had a nursing school at Fauabu on Malaita. The SSEM began girls' schools at Afio, Araki and Gwaidingale, and a midwifery school at Nafinua in east Malaita. The Methodist Mission established Goldie College, and an Adventist school was begun at Kukundu. The first girl to attend the government's King George VI School at Aligegeo began her studies in 1959, facing much opposition. Two more, Joy Baera from Kokomu and Hellen Gelitoa from Ambu, attended the school from 1963 as day students. When the school was relocated to Kukum (Panatina) in Honiara, only five of the 159 students were female. (Pollard and Waring 2010, 13-14)

In 1951, the Department of Education consisted of a Director, one inspector, one European primary school teacher, six local teachers and one clerk. Using a Colonial Development and Welfare grant, five elementary schools were opened on Malaita at the end of 1952, employing local teachers, and several were opened in other parts of the Protectorate the next year. The Department also began mass literacy campaigns in 1951 in Kia on Isabel and at Hauhui on Malaita. (AR 1949-1950, 2-24, AR 1951-1952, 4, 6, 24) In 1953, the Department of Education was expanded to include the Director, a senior education officer, two education officers, one primary school teacher, six indigenous schoolteachers and one indigenous clerk. One European clerk was added in 1954. The initial cost of Protectorate elementary schools was met from Colonial Development and Welfare funds, but from 1960 they became fully the responsibility of the Protectorate. (AR 1955-1956, 5)

Primary education could involve seven years: two at a district school, three at a central school, and two at a senior school. These levels were called Standards (Grades) I to VII. In village schools, most instruction was in local languages and the teachers were untrained. Most of the students were boys, but there were two boarding schools for girls, which emphasized domestic science and mothercraft. In 1956, there were 109 registered schools in the Protectorate: eight government schools; nine Local Council schools; one Chinese school; thirty-seven Anglican (Melanesian Mission) schools, thirty-six Catholic schools, twelve Adventist schools, three Methodist schools and three SSEM schools. There were another two hundred schools that were exempt from registration. There were 105 registered teachers (divided into four grades), and 164 approved teachers who were untrained and had only primary education. The number of schools increased quickly; in 1960, there were 279 registered schools: ten government schools; six Local Council schools, two Chinese schools, sixty-four Anglican schools, fifty-four Catholic schools, twenty-six Adventist schools, 111 Methodist schools, and six SSEM schools. There were 138 registered teachers and 491 approved teachers. (AR 1959-1960, 36-37) Grants were made to missions and Local Councils for designated primary schools containing an agreed number of qualified teachers and an approved student/teacher ratio.

The best schools in the Protectorate were King George VI School (q.v.) at Auki, Malaita, the Anglican St. Barnabas' School, Alangaula (q.v.) and All Hallows' School, Pawa (q.v.), both on Ugi in the Eastern Solomons, and the Catholic Mission school at Tenaru on Guadalcanal. The Methodist Mission had three large co-educational schools in the Western Solomons, the best at Kokeqolo. The Adventists had two co-education schools, one in the Western Solomons and one at Betikama on Guadalcanal. Fees were payable at King George VI School and at the larger mission schools. The best mission schools provided education up to Standard VII, but only the Anglicans and the Catholics provided schools for girls up to Standard VII. (AR 1955-1956, 31-33, AR 1959-1960, 35)

The Legislative Council (q.v.) in early 1963 approved a White Paper on Educational Policy which provided a guide for educational progress until the early 1970s. The intention was to provide a flow of educated Solomon Island leaders, including an adequate supply of teachers upon which to rely for the eventual extension of primary education. The interim system envisaged would be grounded in twenty-two senior and a corresponding number of junior grant-aided primary schools feeding into one full-range co-educational secondary school. At this stage, there were 407 registered schools: six government schools, seven Local Council schools, one Chinese school, eighty Anglican Diocese of Melanesia schools, fifty-six Catholic schools, ninety-one Adventist schools, ninety-one Methodist schools, fifty-four SSEM schools, one Christian Fellowships school, and the company-run Yandina School. In addition, another ninety schools were exempt from registration for another two years. At the end of 1964, there were 165 registered teachers (plus thirty Standard III teachers about to graduate) and 643 approved teachers. (AR 1963-1964, 42-43) The Annual Report statistics for 1969 do not differentiate between types of teachers, and record 1,213 teachers in the Protectorate: 950 males and 263 females, spread between the following school authorities: Diocese on Melanesia (227); Catholic (185); United Church (204); Adventist (192); SSEC (137); Christian Fellowship Church (40); government and Council (102). (AR 1969, 139)

A new White Paper was drawn up in 1967 and put into effect in 1968. Its main features were an expansion of teacher training and payments of equipment and boarding subsidies for scheduled schools. It proposed that after five years there would be 150 junior primary schools in the Protectorate, together with senior primary classes which would offer three years of further education to about 50 percent of the children who reached Standard IV. This would lead to an increase in the number of staff for the British Solomon Islands Training College which would introduce courses for selected Standard IV teachers, and a new system of scheduled schools which would under certain circumstances qualify for subsidies. There would also be increased support for church secondary schools. The plan was to have 150 junior primary and thirty-five senior primary schools by 1973, fully staffed by trained teachers, with subsidies for salaries and boarding grants for students at the senior primary schools. (AR 1967, 47, AR 1971, 56; NS 20 Oct. 1967)

Government expenditure on education increased rapidly, from $613, 533 in 1968 to $1,011,070 in 1970; overall the 1968 figure was 8.96 percent of the government budget, which increased to 15.46 percent in 1970. (AR 1970, 50) In 1970, primary school was a seven-year course divided into Junior (Standards I-IV) and Senior (Standards V-VII). Children were encouraged to begin primary school at age seven. The Senior Primary classes were expanding, with 5,513 students attending throughout the Protectorate: 1,638 (29.7 percent) were girls and 3,875 were boys. The highest proportion of girls at senior primary schools was found in Western District (37 percent) and the lowest proportion was in Malaita District (21 percent). (AR 1970, 50)

Primary Education in the 1970s

The scheduled senior primary schools and many of the scheduled junior primary schools had trained teachers on their staff, but many of the unscheduled church junior schoolteachers remained untrained and consequently standards were low.

1971 Junior Primary Classes

| District | Boys | Girls | Total |

| Central | 2,170 | 1,790 | 3,960 |

| Malaita | 2,091 | 917 | 3,008 |

| Western | 1,163 | 1,624 | 2,787 |

| Eastern | 1,134 | 653 | 1,787 |

| TOTAL | 6,558 | 4,984 | 11,542 |

1971 Senior Primary Classes

| District | Boys | Girls | Total |

| Central | 1,349 | 629 | 1,978 |

| Malaita | 1,126 | 289 | 1,415 |

| Western | 1,055 | 776 | 1,831 |

| Eastern | 700 | 189 | 889 |

| TOTAL | 4,230 | 1,883 | 6,113 |

Source: AR 1971, 57-58

Secondary Education

Secondary education began at King George VI School (q.v.) in January 1958, and the school became fully a secondary school in 1962. A Senior Certificate examination was introduced for students completing their primary education at Standard VI level. A 'Credit Level' was necessary to be eligible to enter secondary school. King George VI School was a boarding school and provided a four-year course up to the Cambridge Overseas School Certificate level. The intake was from government and church senior primary schools. There were also four non-government secondary schools for classes up to Form II: All Hallows', Pawa, St Joseph's Tenaru (boys), Goldie College in New Georgia (co-educational), and St. Mary's at Pamua (girls). By 1969, there were six church secondary schools: St Paul's at Aruligo (Catholic), Su'u on Malaita (SSEM), Goldie College (United Church), Betikama in Honiara (Adventist), All Hallows' Pamua and St. Mary's Pawa (q.v.) (Diocese of Melanesia). At the end of 1969 the last two combined into a new school, Selwyn College, some twenty-nine kilometres from Honiara. (AR 1969, 47) Betikama Adventist School introduced Form II in 1968 as part of plans to extend to Form III in 1969 and Form IV in 1970, as a full secondary school. (NS Dec. 1967)

By mid-1969, there were 749 students enrolled in secondary schools, taught in schools controlled by the following authorities: Diocese of Melanesia (151 boys and 53 girls); government (212 boys and 69 girls); Catholic (107 boys and 19 girls); Adventist (113 boys and 35 girls); SSEC (53 boys); a United Church (56 boys and 29 girls). (AR 1969, 136) Candidates for the Cambridge Overseas School Certificate steadily increased during the 1960s from fourteen in 1963 to sixty-seven in 1970. The standard of results also increased. (AR 1970, 51)

Selection tests for entry to secondary school took place in September each year and were published in October. The 1971 enrolment was 316 and at the end of that year there were twenty staff. In that year, too, there was a changeover to a five-year course of education at the secondary level. (AR 1971, 58)

Teacher Training

The British Solomons Training College (q.v.) opened in 1959. In 1964, a two-year course of secondary education was provided at four church schools, two for boys, one for girls, and one co-educational. At the Catholic Training Institution, at Vutulaka on Guadalcanal, ten female students qualified as Standard III teachers in 1964, bringing the total to twenty since training began in 1961. (AR 1963-1964, 45)

Education Overseas

Missions sent the first Solomon Islanders overseas for education, followed by scholarships from the Protectorate Government and other sources. Large-scale overseas education began in the early 1950s. Government scholarships enabled students to attend schools such as Queen Victorian School in Suva, Fiji, and Te Aute College and Queen Victoria Maori Girls' School in Auckland. A small number attended secondary schools under mission arrangements, in the Territory of Papua and New Guinea, Australia and New Zealand.

In December 1949, the government began a scheme to provide for the beginning of secondary, technical and university education for selected Solomon Islanders, who were at that time mainly staffing schools and the Protectorate administration. During 1949 and 1950, one youth was attending secondary school in New Zealand, and two were at the Queen Victoria School in Suva. One of the latter later went on to the Nasinu Teachers' Training College, also in Fiji. (AR 1949-1950, 7) In 1951, Michael Aike from Malaita (in 1966 ordained as the first indigenous Solomon Islands Catholic priest) arrived at St. Peter Chanel College in Rabaul in East New Britain. By the time he sat for his Queensland Junior examination there in 1961 eight other Solomon Islanders were there. Francis Labu from St. Joseph's School Tenaru joined them that year. In 1962, the Methodist Mission opened Raronga Theological College outside of Rabaul, and twelve Solomon Islanders were part of the first intake.

The first Solomon Islanders to receive government scholarships for tertiary education overseas were Francis Talasasa (q.v.) from Roviana, who gained his New Zealand B.A. degree in 1958, and Norman K. Palmer (q.v.), who completed teacher training and began work in 1958 as a teacher at King George VI School (q.v.) on Malaita. Government scholarships also sent Hugh Paia (q.v.) from the Western Solomons and Lilly Ogatina (later Poznanski) (q.v.) from Isabel to school in New Zealand, and Gabriel Foliga (q.v.) to school in Fiji. (NS Sept. 1958, Nov. 1958) The scholarship holders for 1959 were Effie Kevisi, Agnes Ludavavini, Isaac Qoloni (q.v.), and Edward Iamae. In 1960, Joel Donia from Isabel and Lino Hanaipeo were selected for five-year apprenticeships in Electrical Trades at Suva. Malaitan Jathaniel Wally, Ini Tanata from Tikopia and James Cook from New Georgia went to Rabaul for a three-year training course in metalworking. Caroline Wheatley and Ruth Tiro, both from the Western Solomons, won scholarships for secondary education in Australia and New Zealand, respectively.

The government's scholarships for overseas secondary education in 1962 went to three girls: Helen Ani'i and Doreen Kuper, from the Melanesian Mission's St. Mary's School in Pamua, and Suhote Sikihi from the SSEM school at Afio. Eight boys were chosen to attend the Idubada Technical Training School at Port Moresby. Daniel Maeke, an assistant teacher at the government's Mataniko Primary School, attended a course at Birmingham University, and Maurice Tinoni, an assistant teacher at St. Mary's Melanesian Mission School at Maravovo, attended a course at Reading University. By 1963, forty students were being educated overseas on government scholarships. Twenty-two were in New Guinea and two were in Fiji receiving trade training. One man and one woman were in teacher training institutions in New Zealand, two boys and five girls were at secondary schools in New Zealand, and seven girls were enrolled at Australian secondary schools. Many others were being educated overseas on mission scholarships; about twenty-five Adventist students were in Rabaul, and many Melanesian Mission and Methodist people were being trained in New Zealand. In that year, thirteen out of the forty scholarships awarded went to women: one woman went to teachers' training college, seven to secondary schools in Australia and five to secondary schools in New Zealand. Two women-Imogene Vida from Marovovo on Guadalcanal and Mary Vava from St. Mary's School-were also sent to Suva for home economics training. Ella Bugotu (q.v. Francis Bugotu) received a scholarship to study domestic science at Edinburgh College, and Veronica Teutalei, a teacher as St. Mary's School, undertook a primary education course at Cambridge University. Late in 1963, the first Adventist women teachers returned from their training in Papua New Guinea. (Pollard and Waring 2010, 17)

By the mid-1960s nearly three hundred young Solomon Islands men and women were studying overseas on church and government scholarships, about one in every five hundred people in the Protectorate. Around 190 were studying under the auspices of the various churches. More than half were in secondary schools in Australia and New Zealand. In 1966, the churches alone provided overseas scholarships for 132 students. During 1967, thirty-one students were taking technical training courses overseas: twenty-seven in Papua New Guinea and four in Fiji. Two others were taking clerical courses overseas. In 1969, three students matriculated from Preliminary Year and four students completed second-year studies at University of Papua New Guinea. Similar numbers were studying at the University of the South Pacific, and by 1971 there were about thirty Solomon Islander students there. This generation of students rose to become important leaders of the independent nation in the 1970s. (AR 1967, 51, AR 1969, 50)

When universities were established in the Pacific in 1960s, Solomon Islands students began to attend them. The first to go for University of Papua New Guinea's Preliminary Year were Augustine Manakako, Geoffrey Beti (q.v.) and Aquila Talasasa in 1966. They were followed the next year by Wainga Taniera, Wilson Ifanaoa, John Selwyn Saunana (q.v.), John Sau and George Tuke. Francis Saemala (q.v.), David Kera, John Lamani, Alfred Selwyn, Jimmy Hilly and Francis Billy Hilly (q.v.) were sent to the University of the South Pacific. In 1968, another five students joined them. (NS 31 Jan. 1963, 1 Mar. 1964, 21 Mar. 1966, 7 May 1966, 21 Aug. 1967, 31 Jan. 1968; AR 1967, 50)

Twenty-six BSIP workers completed professional training overseas in 1970, and another thirty were still abroad. The numbers increased rapidly as localisation was pushed through all sectors. By 1971, ninety Protectorate-sponsored students were overseas, along with another eighty-eight sponsored by the missions and twenty-nine by trusts, private enterprise and international agencies. These students were scattered widely across the Pacific, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Students attended the University of the South Pacific, the Fiji School of Medicine (in several capacities), and the Technical Institute in Fiji, and in Papua New Guinea, Vudal and Popondetta Agricultural Colleges, Goroka Teachers' College, Bulolo Forestry College and the University of Technology and Lae Technical College in Lae, and P&T College and the Legal Training Institute in Port Moresby. (AR 1970, 54-55; NS 1971, 62) In 1974, the overseas institutions attended remained the same but many more students went to them, 110 in all. Forty-one were pursuing degrees, thirty-seven diplomas and twenty-five certificates. A few undertook Preliminary Year in Arts (2) and Science (5) at Papua New Guinea universities. (AR 1974, 71-73)

1970s

In December 1973, an Education Policy Review was tabled in the Governing Council (q.v.). It set in train a series of consultations that led to a White Paper being introduced into the new Legislative Assembly (q.v.) in October 1974. In August 1974, a ministerial system of government was introduced and the Education Department was replaced by a Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs, with a portfolio that included Libraries, Museum Services, Sociological Research, the National Archives, Church Affairs and Tourism.

The White Paper was partly a result of some of the major churches deciding to relinquish direct responsibility for primary education in 1975. The result was that education spending was increased from 16 percent to 18 percent of the national budget and the Ministry of Education had added 'Cultural Affairs' to its title and responsibilities. Previously, the government had concentrated on secondary schooling and technical and teacher education, tertiary training being met by overseas aid donors. Honiara Technical Institute (q.v.) continued to serve the Protectorate, with about 10 percent of its enrolments coming from other Pacific territories. Its courses were aimed at lower to middle management, and students of higher technical training, and degree and diploma training, usually went to Fiji or Papua New Guinea. Councils and churches ran other lower-level courses.

Until 1975, primary education was a seven-year course divided into Junior (Standards I-IV) and Senior (Standards V-VII). The usual Standard I starting age was seven years. Schools were known as 'scheduled' (which met a certain class size and teacher qualifications and received government funding support) and 'unscheduled' (where staff were untrained).

| Central | Malaita | Western | Eastern | TOTAL | |

| Scheduled | 6,762 | 3,388 | 6,331 | 3,372 | 19,853 |

| Unscheduled | 1.029 | 1,090 | 1,395 | 748 | 4,262 |

| TOTAL | 7,791 | 4,478 | 7,726 | 4,120 | 24, 115 |

In 1974, 17,301 students attended junior primary schools: 10,162 boys (58.7 percent) and 7,139 girls (41.2 percent), with the largest enrolments in the Central and Western districts. There were 6,814 students in senior primary schools, and at this level the percentage of girls declined: 4,363 boys (64 percent) and 2,451 (35.9 percent) girls. Once again, the largest numbers of students were in the Central and Western districts. The Sixth Development Plan made provision for expanding secondary education, with recurrent capital grants to subsidise teachers' salaries. King George VI School produced thirty-six school certificates with a 69 percent pass rate, Selwyn College five with a 29 percent pass rate, Catholic schools four with a 50 percent pass rate, and Betikama Adventist School produced six with a 27 percent pass rate. (AR 1974, 12)

Related entries

Published resources

Books

- Bennett, Judith A., Wealth of the Solomons: A History of a Pacific Archipelago, 1800-1978, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 1987. Details

- Kenilorea, Peter, Tell It As It Is: Autobiography of Rt. Hon. Sir Peter Kenilorea, KBE, PC, Solomon Islands' First Prime Minister, Clive Moore, Centre for Asia-Pacific Area Studies, Academia Sinica, Taipei, 2008, xxxvi, 516 pp. pp. Details

- Laracy, Hugh M., Marists and Melanesians: A History of the Catholic Missions in the Solomon Islands, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1976. Details

Edited Books

- Pollard, Alice A., and Waring, Marilyn J. (eds), Being the First: Storis Blong Oloketa Mere Lo Solomon Aelan, RAMSI and Institute of Public Policy and Pacfici Media Centre, AUT University, Honiara and Auckland, 2010. Details

Journals

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate (ed.), British Solomon Islands Protectorate News Sheet (NS), 1955-1975. Details

Manuscripts

- Boutilier, James A., The Role of the Administration and the Missions in the Provision of Medical and Educational Services in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, 1893-1942, Anglican Church of Canada, Church House Library, Toronto, 1974, 75 pp. Details

Reports

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate, British Solomon Islands Protectorate Annual Reports (AR), 1896-1973. Details