Place: Guadalcanal Island

- Alternative Names

- Gold Ridge

Details

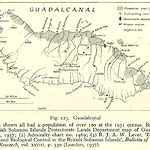

Guadalcanal Island is about 144 kilometres long, and 48 wide across the centre. The island has a northwest-southeast axis and its interior consists of rugged mountain ranges. It is the highest island in the Solomons, with Mt. Popomanaseu reaching 2,449 metres (8,035 feet). The central ranges drop steeply to the coast in the south, and less steeply in the foothills and plains on the north coast. The north side is relatively dry for about half of the year. The southern side receives rain from the southeast trade winds and is pounded by strong seas. The southern coast is cut by many steep valleys holding rivers that can become raging torrents in heavy rains. On this side, the coastal plain is narrow to non-existent, the sands are black and there are few inlets or safe harbours. It is known locally as the Weathercoast or Tasi Mauri (active sea). The sheltered northern side of the island is known locally as Tasi Mate (dead sea) since it does not receive the large swells delivered along the south coast. Gallego is a series of volcanic cones in northwest Guadalcanal. One of these, Mt. Esperance, may have been active within the last two thousand years.

The island has experienced severe earthquakes, landslides and mudflows. In July 1965, after heavy rain, half the mountains along the coast near Avuavu on the Weather Coast experienced landslips, some villages disappeared entirely and many gardens were destroyed. Soon after, in February 1967 heavy rain caused large landslides in central Guadalcanal, some of them more than three hundred metres long, which carried tops of ridges down mountain sides. On 21 April 1977 earthquakes caused the biggest land movement in memory. Guadalcanal has few harbours and the only all-weather harbour is at Marau Sound. (Webber 2011, 223-228; NS 7 Dec. 1967)

Fifty kilometres east of Honiara, the Guadalcanal Plains (q.v.) stretch from the coast to the foothills. They have the most fertile soils and are the largest area of flat land in the Solomons. The plains stretch thirty kilometres along the coast and reach up to eight kilometres inland. They were previously a patchwork of tall grass, with rainforest along the rivers, and gardens. This area was selected for coconut plantations in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and local people often received scant compensation for their land. The government claimed a large portion of this land after the Phillips Land Commission in 1911, but local villagers disputed this. The plains are quite low-lying and can be submerged by heavy rains: in 1966 the whole plain was under water to a depth of about a metre, leaving villagers marooned in their houses and even sheltering in trees. Koleula River, in particular, can become a raging torrent sweeping boulders along its bed.

The earliest archaeological evidence of human settlement south of Buka Island is at Vatuluma Posovi in Guadalcanal's Poha Valley. People lived there 6,400 years ago and used a cave beside the Poha River for occasional shelter. Signs of cooking fires, broken stone and shell tools, and items of jewellery such as shell rings and beads remain. The people lived on wild foods and what they could collect or hunt. There is no evidence of gardening or domesticated plants or animals in the Solomon Islands until after 3,200 years ago. (Roe 1992)

There may never have been one local name for Guadalcanal as there was for Isabel Island and probably Malaita. As a large island, it may have been similar to some its other neighbours in having names only for its regions. The Moro Movement (q.v.) used the name Isatabu for Guadalcanal and modern Guadalcanalese and other Solomon Islanders have begun to use 'Guale' as a short descriptor for the people. The development of Honiara and the Guadalcanal Plains in the second half of the twentieth century brought heightened attention to land matters on Guadalcanal, and land issues became part of the 'tension' between 1998 and 2003. (Moore 2004; Fraenkel 2004; Naitoro 2000, 2002; Naitoro et al. 2000b; Kabutaulaka 1998, 1999, 2000a, 2000b, 2003a, 2003b, 2004, 2005) A Commission of Inquiry into Land Dealings on Guadalcanal began in 2009 and presented its finding in 2012.

Given land's political importance, it is worth summarizing in some detail earlier assessments of land and social relationships. The historical record has preserved various accounts of the Guadalcanal's tribal and totemic divisions, which differ only slightly. With the exception of the people of Marau Sound who originated in (and maintain close links with) 'Are'are on Malaita, the people of Guadalcanal are matrilineal in their organisation of land matters. In the late 1930s, District Officer Dick Horton perceived them as having two separate cultures related to two totems: 'the Garavu (the fish hawk) and the Manukiki (the eagle), and six clans, which between them cover the island. Only the people of Marau Sound, who are patrilineal and worship the white pig, have no clan system'. (Horton 1965, 130) In researching land tenure during the 1950s for the Report of the Special Lands Commission on Customary Land Tenure (1957), Colin Allan defined the same two exogamous moieties, along with associated clans. Under Manukiki, Allan listed Haubatu, Lakuili and Kiki clans in the north and Gaubatu, Thonggo and Naokama in the west and northwest. Under Garavu, Allan listed Zimbo, Kidikali and Kakau clans in the north and Thimbo and Lathi in the west and northwest. He continued:

In the south, east and central Guadalcanal, the two major groups (rau) constitute moieties with which are associated a varying number of component clans, called raundakendake. The numbers vary from place to place. In the Marau bush for example, there are twelve, while at Avu Avu there are four only. At Talise on the other hand, Manukiki has thirty-four while Garavu has thirty two. There have been two curious developments at Talise and Malango/Vulolo. One is the emergence of the garavu vetale or garavu 'half-line' as it is called in pidgin English. This consists of three clans, the members of which, for the purposes of marriage, regard themselves as constituting a separate exogamous moiety. The 'half-line' is said to have originated because a member of the garavu moiety offended against the exogamous principle and refused to acknowledge his error. By ceremonial distribution of food, 'half-lines' can be translated to conventional status. This second development is the establishment in certain areas of the Haubata clan as a separate rau. This has resulted from migrations from west and north-west Guadalcanal. (1957, 65)

In evidence presented to the Commission of Inquiry into land on Guadalcanal (25 Mar. 2010) Waeta Ben Tabusasi (q.v.) declared that there were originally two 'tribes', Garesere (his own clan) and Garavu, and that 'clans' sprang out of these, which is similar to Horton's 1930s description. While the count varies, clearly there are totemic groups that exist across most of Guadalcanal and they are exogamous. The terms kema (for totemic group) and mamata (tribe or clan) are used in north Guadalcanal. Descriptions often mix up their usage of 'totem', 'tribe' and 'clan'. In the Tasi Mauri area there are four kema, known as Qaravu, Manukiki, Koniahao and Lasi. The Moro Movement creation myths give a similar account. There is a fifth kema, Thimbo (Simbo), which is usually thought to be different from the other four. In the other languages of Guadalcanal, different names refer to the same tribes; for example, in Tasimboko (Tathimboko or Tadhimboko) on the Tasi Mate coast the main clans are Lathi, Ghaobata, Nekama and Thimbo. Tarcissius Tara Kabutaulaka notes that although the names are different, the totems are the same. 'According to the beliefs of the Guadalcanal people, those who share the same totem are related, and marriage within the same tribe is not allowed even if the potential partner is from a different part of the island and speaks a different language. As long as their tribes share the same totem, they are related'. (Kabutaulaka 2002, 25) Below these tribes are mamata (also called ulu ni beti) or clans or descent groups with district lands and rights, and these form the basis of landowner status. The presence of totemic groups crosscutting language and tribal groups is unlike the situation on neighbouring islands such as Malaita or Makira, although there are closer similarities on Isabel Island and in the Western Solomons.

Like the other islands in the archipelago, Guadalcanal also needs to be considered in the context of its neighbours. There was a complex world of trading and raiding bound together at both spiritual and physical levels. The Marau area shows the clearest outside influence. It consists of lagoons and passages around small islands, and the area was settled by migrants from the 'Are'are area opposite on the west coast of Malaita. This was thirteen generations ago, though some claims go back thirty-four generations. Certainly, there were 'Are'are at Marau when the Mendaña expedition visited in 1568, and trade and kinship links always meant there was canoe traffic back and forth to Malaita not only to 'Are'are but also to Langalanga, which produced shell currency used in Marau. Marau Sound was also used by Malaitans as a base from which to attack Makira. Large numbers of 'Are'are settlers seem to have arrived after the 1860s when a dysentery epidemic reduced the number of coastal people at Marau. (Horton 1965, 131; Bennett 1974, 16; QSA COL/A783, Douglas Rannie to Immigration Agent, 19 Dec. 1892, enclosed in in-letter 855 of 1893 to Colonial Secretary to Governor, 20 Feb. 1893) The Marau people were divided between those living on the islands in the sound and those living on the mainland.

Headhunters (q.v.) from the Western Solomons and the Russell Islands raided Guadalcanal's northwest coast, while people from Nggela and Savo traded with and raided the north coast. Horton mentions the Kakau clan, which is strong on Guadalcanal and Nggela, and the Thimbo (Simbo) people of Guadalcanal who are linked to the island of Simbo in the Western Solomons. Marau Sound also has a spiritual significance since the island of Malapa (Marapa) is said to be the resting place of the ghosts of the dead from parts of Malaita, Guadalcanal and Nggela, although some of these spirits eventually return home. (Horton 1965, 131; Kenilorea 2008, 39)

Guadalcanal people would have been aware of European whalers and traders who began to pass by in the 1790s. These contacts intensified in the 1820s and 1840s, although mainly in the Western Solomons and Makira. Headhunting from the 1860s to the 1890s, mainly from New Georgia but also from Russell Islands and Savo, was exacerbated by the influx of trade goods, and there were raids on the west coast of Guadalcanal at Wanderer Bay in the final decades of the century. Survivors from these raids retreated southward from the north coast. (Bennett 1974, 29, 37-40) Wanderer Bay was named after a ship of that name owned by Australian-based British adventurer and entrepreneur Benjamin Boyd who was murdered there on 15 October 1851 when he went ashore to shoot game. There were rumours in Australia that Boyd was still alive and HMS Herald and the Oberon were sent to search for him. (Prendeville 1987; Diamond 1988) Bishop Patteson (q.v.) first visited Guadalcanal in 1857 and took two students from the northwest back to New Zealand with him.

There was another fatal European incursion in 1895 related to the Austrian-Hungarian naval gunboat SMS Albatros under Commander von Mauler, accompanied by Baron Foullon von Norbeck, Director of the Imperial and Royal Geological Society in Vienna. An expedition of eighteen set off into the mountains guided by Saki from Tetere. They were attacked on 10 August as they tried to ascend the highest mountain, which they knew as Tatube (Tatuve), which had a guardian spirit named Momolo. There were several deaths on both sides of the attack, and the remainder of the European party made their way back to their ship. The Albatros sailed to Marau Sound to help in recuperation and then left for Australia. In August 1896, Resident Commissioner Woodford spent nearly three weeks on Guadalcanal investigating the attack and several years later the Austrians sent the cruiser Leopard to erect a monument to those killed, which remains today. (http://mateinfo.hu/a-albatros.htm [accessed 12 July 2011])

There was early European trading and plantation development in the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s around Marau Sound and along the sheltered north coast, particularly along the Guadalcanal Plains. (Bennett 1974, 74-75, 136) The first foreign traders-James Robinson, his brother William and possibly A. H. Smith-arrived in 1877, all working for the New Zealand company Henderson and Macfarlane. (Clark 2011, 221-231) For several months they traded at Ruavatu, Rua Sura Island, Rere, Kaoka and at Marau Sound. Plantations were established along the coast from Kokomunka in the northeast right along the Guadalcanal Plains and around to Marau Sound. Marist Catholic (q.v.) missionaries arrived at Aola in 1898 and purchased Rua Sura Island from a local European planter as their base. From there they moved along the Weathercoast to Avuavu and Tangarare, and by 1904 to the island's western end at Visale (q.v.) began visiting Guadalcanal in the 1890s and by 1903 had installed a teacher in the northwest of the island. (Bennett 1974, 85-86) The South Sea Evangelical Mission (q.v.) followed after some of its Queensland Kanaka Mission (q.v.) Christians from Guadalcanal returned home in 1906-1907.

All of this development introduced trade goods and began to alter the pre-contact balance between descent groups. Guadalcanal men and some women were also major participants in the indentured labour trade to Queensland (4,188 between the 1870s and 1903), Fiji (1,214 between the 1870s and 1911) and internally in the Solomons (8,332 between 1913 and 1940). (Price with Baker 1976; Siegel 1985; Shlomowitz and Bedford 1988; Bennett 1974, 48-72) These external and internal labour trades began in the 1870s, initially often involving illegality, and then changed over decades to voluntary enlistment. The whole labour reserve over generations came to accept indentured labour work away from home as normal for a young man. One effect of this circular migration was an introduction of European manufactured goods and, particularly important in the nineteenth century, the introduction of guns, mainly Snider rifles. These altered the power balance between descent groups and made some bigmen more powerful. (Bathgate 1978, 11) Guadalcanal's labour trade from the 1870s through the 1940s was second in size only to Malaita's.

Marau Sound on the island's eastern end is the only area of the island with an all-weather anchorage and beginning in the 1890s it attracted early traders such as Captain Karl Oscar Svensen (Captain Marau). (Bennett 1981) The first government station was established at Aola in 1914 on the north coast opposite Malaita, and Aola was also the port for overseas shipping services. Just before the Second World War, Aola consisted of the District Officer's house and a Chinese trade store. The villages of Luvanabuli and Balo were close by, and the nearest European neighbours were Inge and Ernie Palmer at Bara plantation. A Lever Brothers' plantation was at Rua Vatu, about sixteen kilometres away, and a Catholic mission station was nearby. Guadalcanal was home to more Europeans than any other island in the Solomons, but they were spread around the island and had little contact with each other. A network of unofficial headmen was established in 1916-1917. (Horton 1965, 129-130; Bennett 1974, 97) The introduction of a Head Tax of 10/- per able-bodied man in 1922 also caused major changes and forced many men into indentured labour on local plantations and plantations in the Western Solomons and Isabel. In 1925, there were 15,138 acres under coconuts and 5,058 head of cattle on Guadalcanal, centred along the north coast. Guadalcanal people could get cash through indentured labour and by supplying crops to the plantation, mission and government stations. Recruiting and trading schooners plied the coast. Copra production slipped back during the Depression years of the 1930s and wage rates were halved; the Head Tax was not reduced to reflect this. (Bathgate 1993, 62, 74)

Today Guadalcanal is the site of the only gold mine in the Solomons, at Gold Ridge in the centre of the island. It began as a centre for alluvial mining in the 1930s. This was not the first time gold had been found on the island. In the sixteenth century the Mendãna expedition, searching for the source of King Solomon's fabled wealth, found traces of gold on Guadalcanal. Much later, in 1896, samples gathered from Guadalcanal showed high quantities of gold and copper, and this encouraged further exploration in 1930-1931, when payable quantities of gold were discovered by the botanist S. F. Kajewski from the University of Queensland. This find attracted small-scale prospectors to alluvial claims on the Tsarivonga and Sorvohio Rivers and at Gold Ridge, and then later in the Sutakiki River beyond Gold Ridge. In 1941, Queensland mining entrepreneur E. G. Theodore, of Fiji's Emperor Mine, began Solomons Gold Exploration Ltd. and was awarded a prospecting agreement over one-third of Guadalcanal, but the war halted operations.

There were many plantations around the coast of Guadalcanal, from Kokomuruka and Hoilava on the northwest coast to Nughu, Taievo and Lavuro just south of Maravovo, then a string along the Tasi Mate coast: Tanaemba, Aruligo, Ndoma, Tambaleho, Tanakombo, Ruaniu and Mamara west of Point Cruz (the modern port for Honiara); Kukum, Lungga, Tenaru and Muvia between Point Cruz and Ngalimbiu River; Tetere (Gavaga), Ilu, Tenavatu, Mberande (Penduffryn), Taivu and Ruavatu along the Tasimboko (Tadhimboko) coast; Tuvu, Manisagheva (Aola), Ivatu and Rere, all near Aola; Kaoka (Kaukau) and Maraunia around Kaoka Bay; and Symons, North, Tavanipupu and Paruru at the Marau Sound end of the island. (Bennett 1987, 136; Golden 1993, 117-122)

The biggest changes on Guadalcanal came with the Second World War (q.v.) when the Japanese established a base and airfield at what is now Honiara. This was overrun by the Americans, who developed it into their major Solomon Islands base with a considerable infrastructure including several airfields. During and after the war, communications and travel were made easier along the western part of the north coast by roads built by the American forces, and there were also several airstrips near what later became Honiara. One of these strips became Henderson Airfield, the present international entry point to the country. Despite the attractions of Honiara, a sizable population remained in the interior of the island and on the Weathercoast.

In 1946, Theodore's Solomons Gold Exploration Ltd. withdrew, leaving the gold fields to the small-scale prospectors. Then, during 1948 and 1949, the Balasuna Syndicate's leases at Gold Ridge were examined by geologist E. R. Hudson on behalf of Broken Hill Pty. Ltd. In 1952, Bulolo Gold Dredging Co. drilled a portion of the local Balasuna Syndicate's lease on the Kovagombi area of Sorvohio Valley alluvial goldfields, but withdrew because the Territory of Papua New Guinea administration would not extend the contracts of its New Guinea labourers working there. Also in 1952, the Anglo-Oriental (Malaya) Ltd. searched for gold on Guadalcanal and Malaita, and took out prospecting leases on Guadalcanal. A new gold-bearing lode was discovered in 1955 at Gold Ridge, centred on Kuper's Creek. Development of the project was by Clutha Development Co., using twenty-five labourers from New Guinea and forty Solomon Islanders. In 1960, Oil Search Ltd. of Australia made preliminary gravity surveys on the Guadalcanal Plains, which revealed that the plains concealed an uplifted block which divided the potential oil basin. Oil Search withdrew from further exploration, but this concealed structure extended the known gold-producing area.

Local villagers were aware of the value of the gold and began to pan for it and to establish permanent villages around the alluvial sites. A local gold industry developed, with the gold sold to business people in Honiara. Guadalcanal panners officially recovered gold valued at £8,226 in 1965, £8,707 in 1966 and £17,252 in 1967, but presumably the same invisible sales that occur today were occurring then, so these figures should be much higher. (NS 31 Aug. 1968) One 1995 estimate suggests that 30,000 to 60,000 grams of gold were panned at Gold Ridge by local people every year over the decades before large-scale mining began. (Grover 1956, 1963; NS 2 Sept. 1955, 12 Sept. 1955, 7 July 1956, 20 July 1956; Moore 2004, 83-88)

After the war the British decided to transfer their capital from the now-destroyed Tulagi to Honiara (q.v.), drawn by the existing infrastructure there and its proximity to the Guadalcanal Plains. During Maasina Rule (q.v.) (1944-1952), the Marau 'Are'are people were part of the political movement. In 1953, preparations began to form a Guadalcanal Council. In 1954, two of the Marau villages (Hatere and Niu) wanted to join the Malaita Council instead, and when this was rejected they wanted to form their own Marau-Hauba Council. This was allowed in 1955, but it foundered soon afterwards. There was considerable tension between the Marau 'saltwater' people, who were determined to expand their interests on Guadalcanal, and the inland people. The Marau Malaitans claimed to own all of the land from Oniseri to Kaukau. The indigenous Guadalcanal people remain inclined to regard the Malaitans as intruders, despite the hundreds of years that link them all. Similarly, the people on the north side of the island have long-standing kin and trade connections with the inhabitants of Nggela, Savo and Russell Islands, and to a lesser extent with Isabel Island.

Once Honiara was established, Guadalcanal was administered from there with the District Commissioner Central in charge. The Guadalcanal Council was established in 1953, composed of rural Sub-District Councils Malango-Vulolo, Lengo, Birao, Sughu, Visale and Talise. The Guadalcanal Council flag was approved on 9 August 1965; it showed Vatuposau hill, behind Rere, in green, and a large eagle with outspread wings perching atop the hill against a background of blue sea. The background of the flag is brown, symbolizing the earth of the Guadalcanal Plains. (NS 15 Aug. 1965) While the Tasi Mate coast developed, the Tasi Mauri or Weathercoast was neglected in terms of administration and economic development. Even today the Weathercoast is not properly linked into the extreme development on the north coast. The Moro Movement (q.v.) arose as a socio-economic force on the Tasi Mauri coast in the 1950s and remained important until the 1970s and 1980s. (Chapman and Pirie 1974)

One unique feature of Guadalcanal people is their use of vele or piro, a form of sorcery found on the north coast and in the northwest corner of the island, which is feared throughout the Solomons. The power of the vele men was reduced by District Officer L.W.S. Wright in the 1930s when he brought many of them to court for their practices. (Wright 1938-1939, 1940; Bathgate 1985, 85-88; Horton 1965, 157-161; Tedder 2008, 187, 190-192; Allan 1989, pt. 1, 87; Davenport and Çoker 1967)

Related entries

Published resources

Books

- Allan, Colin H., Solomons Safari, 1953-58 (Part I), Nag's Head Press, Christchurch, 1989. Details

- Bathgate, Murray, Fight for the dollar : economic and social change in western Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, Alexander Enterprise, Wellington, New Zealand, 1993. Details

- Bennett, Judith A., Wealth of the Solomons: A History of a Pacific Archipelago, 1800-1978, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 1987. Details

- Chapman, Murray, and Pirie, Peter, Tasi Mauri: A Report on Population and Resources of the Guadalcanal Weather Coast, East-West Population Institute, East-West Center; University of Hawai`i, Honolulu, 1974. Details

- Clark, Jennifer, Kauri, Coal and Copra: 19th Century Voyages of Captain James Robinson around the South Pacific, Jennifer Clark, New Zealand, 2011. Details

- Diamond, Marion, The Sea Horse and the Wanderer: Ben Boyd in Australia, University of Melbourne Press, Carlton (Vic.), 1988. Details

- Fraenkel, Jon, The Manipulation of Custom: From Uprising to Intervention in the Solomon Islands, Victoria University Press, Wellington, New Zealand, 2004. Details

- Golden, Graeme A., The Early European Settlers of the Solomon Islands, Graeme A. Golden, Melbourne, 1993. Details

- Horton, Dick C., The Happy Isles: A Diary of the Solomons, Originally published: 1965, Heinemann, London, 1965. Details

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius T., Pacific Islands Stakeholder Participation in Development: Solomon Islands, Pacific Islands Discussion Paper Series No. 6, World Bank, East Asia and Pacific Region, Papua New Guinea and Pacific Islands Country Management Unit, Washington D.C., September. Details

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius T., Footprints in the Tasimauri Sea: A Biography of Dominiko Alebua, Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, Suva, 2002. Details

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius T., A Weak State and the Solomon Islands Peace Process, East-West Centre Working Papers: Pacific Islands Development Series No. 14, University of Hawai'i at Manoa; East-West Center, Honolulu, 2003a. Details

- Kenilorea, Peter, Tell It As It Is: Autobiography of Rt. Hon. Sir Peter Kenilorea, KBE, PC, Solomon Islands' First Prime Minister, Clive Moore, Centre for Asia-Pacific Area Studies, Academia Sinica, Taipei, 2008, xxxvi, 516 pp. pp. Details

- Naitoro, John H., Solomon Islands Conflict: Demands for Historical Rectification and Restorative Justice, Asia Pacific School of Economics and Management Update Papers, June 2000, Asia Pacific Press and Australian National University, Canberra, 2000a. Also available at http://peb.anu.edu.au. Details

- Naitoro, John H. et al., The Solomon Islands Reconciliation and Rehabilitation Project, Solomon Islands Reconciliation and Rehabilitation Project Planning Committee, Canberra, 8-Mar-00. Details

- Tedder, James L.O., Solomon Islands Years: A District Administrator in the Islands, 1952-1974, Tuatu Studies, Stuarts Point, NSW, 2008. Details

- Webber, Roger, Solomini: Times and Tales from Solomon Islands, Troubador Publishing Ltd, Leicester, UK, 2011. Details

Book Sections

- Bathgate, Murray A., 'Movement Processes from Precontact to Contemporary Times: the Ndi-Nggai, West Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands', in Murray Chapman;R. Mansell Prothero (ed.), Circulation in Population Movement: Substance and Concepts from the Melanesian Case, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1985, pp. 83-118. Details

- Grover, J.C., 'A Brief History of the Geological and Geophysical Investigations in the British Solomon Islands, 1881-1961', in Gordon A. MacDonald (ed.), Geology and Solid Earth Geophysics of the Pacific Basin: Report of the Standing Committee, University of Hawai`i Press, Honolulu, 1963, pp. 171-180. Details

- Roe, David, ' Investigations into the Prehistory of the Central Solomons: Some Old and Some New Data from Northwest Guadalcanal ', in Jean Christophe Galipaud (ed.), Poterie Lapita et Peuplement: Actes du Colloque Lapita, ORSTOM, Noumea, 1992, pp. 91-101. Details

Conference Proceedings

- Bathgate, Murray A. (ed.), Pre-Contact, Post-Contact and Contemporary Movement Processes in Western Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, International Seminar on the Cross-Cultural Study of Circulation, East-West Centre, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, 1978, 66 pp. Details

- Grover, J.C. (ed.), Presidential Address, 1954, British Solomon Islands Society for the Advancement of Science and Industry, vol. Transactio, British Solomon Islands Society for the Advancement of Science and Industry, Honiara, 1956, Internal 1-9 pp. Details

Edited Books

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius T. (ed.), Crowded Stage: Actors, Actions and Issues, Securing a Peaceful Pacific, John Henderson;Greg Watson, Canterbury University Press, Christchurch, 2005, 408-422 pp. Details

Journals

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate (ed.), British Solomon Islands Protectorate News Sheet (NS), 1955-1975. Details

Journal Articles

- Bennett, Judith A., 'Oscar Svensen: A Solomons Trader Among 'the few'', Journal of Pacific History, vol. 16, no. 4, October, pp. 170-189. Details

- Davenport, William H., and Çoker, Gülbün, 'The Moro Movement of Guadalcanal, British Solomon Islands Protectorate', Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol. 76, no. 2, June, pp. 123-175. Details

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius T., 'Political Reviews: Solomon Islands', Contemporary Pacific, vol. 11, no. 2, 1999, pp. 443-449. Details

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius T., 'Solomon Islands Search for Peace: The Townsville Peace Agreement', Pacific News Bulletin, November, pp. 4-5. Details

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius T., 'Beyond Ethnicity: Understanding the Crisis in the Solomon Islands', Pacific News Bulletin, May, pp. 5-7. Details

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius T., 'Political Reviews: Solomon Islands', The Contemporary Pacific, vol. 16, no. 2, 2004, pp. 393-401. Details

- Shlomowitz, Ralph, and Bedford, Richard D., 'The Internal Labour Trade in New Hebrides and Solomon Islands, c 1900-1941', Journal de la Société des Océanistes, vol. 86, 1988, pp. 61-85. Details

- Siegel, Jeff, 'Origins of Pacific Island Labourers in Fiji', Journal of Pacific History, vol. 20, no. 2, 1985, pp. 42-54. Details

- Wright, L.W.S., 'Notes on the Hill People of North-Eastern Guadalcanal', Oceania, vol. 9, 1938-1939, pp. 97-100. Details

Manuscripts

- Prendeville, Kerry F., Memories Around a Village Water Supply: A Story of Benjamin Boyd and the Ghari People of Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, Guadalcanal Cultural Centre, Honiara, 1987, 36 pp. Details

Theses

- Bennett, Judith A., 'Cross-Cultural Influences on Village Relocation on the Weather Coast of Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, c. 1870-1953', MA thesis, University of Hawaii, 1974. Details

- Naitoro, John H., 'Articulating Kin Groups and Mines: The Case of the Gold Ridge Project in the Solomon Islands', PhD thesis, Australian National University, 2002. Details

Web Pages

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius T., Oceania's Insecurities: Terrorism Isn't The Only Regional Problem, Lifhaus.com, 2003b. Also available at http://www.lifhaus.com/security.htm. Details

Images

.png)

- Title

- Aloa man smoking a pipe, with a shield and axe, Guadalcanal

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1880s - 1890

- Source

- Woodford 1890

.png)

- Title

- Barakossa, servant of C.M. Woodford, Aloa, Guadalcanal

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1880s - 1893

- Source

- Woodford 1890

.png)

- Title

- Catching rainwater, Village at Maravovo, Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

- Title

- Church at Maravovo, Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

.png)

- Title

- Guadalcanal Boys Shooting Arrows (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

.png)

- Title

- Guadalcanal Women Returning from Work (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

- Title

- Houses at Maravovo, Guadalcanal) (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

.png)

- Title

- Houses at Maravovo, Guadalcanal) (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

- Title

- Inside Church, Maravovo, Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

- Title

- Man with Snider beside skull repository at Marau Sound, Guadalcanal

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1910s

- Source

- Raucaz 1928

.png)

- Title

- Memorial Cross for Pioneer Missionaries of Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

- Title

- Mission House at Maravovo, Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

.png)

- Title

- North-West Guadalcanal from Sea-Nearer View (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

- Title

- Rev. Bollen and Teachers, Maravovo, Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

.png)

- Title

- Street Scene in the Village, Maravovo, Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

.png)

- Title

- Street Scene in the Village, Maravovo, Guadalcanal) (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

.png)

- Title

- The Palm Avenue at Maravovo, Guadalcanal) (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

- Title

- Under the Coconut Trees at Maravovo, Guadalcanal (Solomon Islands)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

.png)

.png)

.png)