Place: Honiara

Details

After the Second World War, the British decided to transfer their capital from the destroyed Tulagi (q.v.) to Honiara, drawn by the existing wartime infrastructure and the proximity to the Guadalcanal Plains (q.v.). 'Honiara' is a Ghari language name for the piece of land west of Point Cruz, the site of today's Yacht Club, the Kitano Mendana Hotel, and the old Government House which is now the site of the Heritage Park Hotel. Naho-ni-ara means 'facing the ara', the place where the southeast winds meet the land. Honiara sits on a curving section of the Guadalcanal coast, with no natural sheltered port other than small Point Cruz. It is now home to around sixty-five thousand people.

The land of present-day Honiara was part of Ndi-Nggai territory and the main villages were at Mataniko and Kakambona to the east and west of the Point Cruz, respectively. The core area is made up of three land leases from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, mainly negotiated before the British Solomon Islands Protectorate was established in 1893. The central area from Point Cruz to Tenaru, known as Kukum or Mataniko, was purchased for £60 of trade goods from Uvothea of Lungga, Allea of Manago and his son Manungo on 7 November 1886, by partners Thomas Garvin Keely, John Williams and Thomas Woodhouse, traders in the Shortlands, New Georgia and Ontong Java. However, this purchase was later disputed when Suala, chief of the Gombata descent group living at Mataniko village claimed that Woodhouse had only purchased the land east of Tanakaki belonging to the Simbo people. The deeds seem to have been renegotiated on 18 December 1896, by Woothia (Uvothea) of Langa (Lungga), Allea of Manago, and his son Manungo. Charles Woodford (q.v.) investigated the purchase in 1902. The area to the west, bordering on Point Cruz, called 'Ta-wtu' or Mamara Plantation, was purchased by Karl Oscar Svensen (q.v.) and his partner Rabuth, and the area to the east, named 'Tenavatu' was purchased by Svensen's employee William Dumphy, apparently late in the first decade of the century. After the Protectorate Government established a lease system, leases on all three areas were sold to Lever's Pacific Plantations Pty. Ltd. (q.v.) as part of a much larger block of land Levers controlled on the north coast. (Golden 1993, 146, 202; BSIP files 18/I/2 and 18/II 5)

In 1919-1920 a Lands Commission was appointed to investigate all previous land alienation in the Protectorate, including claims that purchases on Guadalcanal had been unfair. At this time, as mentioned above, a Mataniko chief named Suala claimed ownership of part of the Honiara land: the Commission recommended that Levers give up part of the land and pay a small sum of money. In 1924 the Secretary of State confirmed the recommendations of the Lands Commission, which gave them force in law. Levers gave up their old title and received conveyance of a smaller piece of land, including the Honiara site. After the war, in 1947, Levers sold the land to the Protectorate Government. In 1964, Baranamba Hoai of Mataniko village claimed ownership of part of Honiara on behalf of himself and the Kakau and Habata descent groups, but the High Court found that the 1924 transfer was still valid.

Second World War

During the Second World War, the site of Honiara became part of a battlefield, first captured by the Japanese, and then by the Americans who established major infrastructure in the area. In early May of 1942, the Japanese reached Tulagi Island, the old administrative capital off Nggela Sule, and attacked the capital and the three adjoining commercial islands, Levers Pacific Plantations Limited's Gavutu-Tanambogo and Burns Philp & Company's Makambo. After heavy air raids on the 1st and 2nd of May, Tulagi fell on the 3rd and the Japanese began to occupy Guadalcanal on 20 June. There they quickly began building an airfield at Lungga and a camp at nearby Kukum, from which they planned to interact with Allied shipping in the Pacific and with operations in nearby New Guinea. The Japanese airfield on Guadalcanal was almost complete when in early August the Americans invaded and secured Guadalcanal, which halted the Japanese southern advance.

Heavy fighting took place all along the Guadalcanal coast, much of it in what is now the centre of Honiara; for several months the surrounds of Mataniko River was a 'no-man's land' between the Japanese and the American forces. Once the Japanese were routed, the Americans set up their main base at Lungga to the east of the present town, although the huge 1st Marine Division was spread over three Levers' plantations: Kukum, Lungga and Tenaru. In late August 1942, Martin Clements, a Protectorate Officer who had become a coastwatcher (q.v.), was instructed by Resident Commissioner William Marchant (q.v.) (evacuated to Malaita) to resume his duties as District Officer of Guadalcanal. By 2 September, the Resident Commissioner was himself based at Lungga and accommodations were worked out between the Allied forces and the Protectorate Government. (Clemens 2004, 204, 221) Point Cruz became a supply and transit base for the Americans and there was a road extending on both sides, thirty-two kilometres east and ten kilometres west-the first real road in the Solomon Islands. From this period until the end of the war, about two thousand Solomon Islanders, most of them from Malaita, worked on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands Labour Corps, with another 680 enlisted for combat duty in the British Solomon Islands Defence Force, working alongside the Americans. (Laracy 1983, 16) In 1946, the war over, the British shifted their headquarters west to use the buildings the Americans had left at Point Cruz. (Tedder 1966, 36)

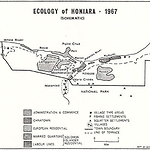

Once Honiara was established, Guadalcanal was administered from there with the District Commissioner Central in charge. On 22 October, at the first postwar meeting of the Advisory Council (q.v.), the formal decision was made to shift the administrative headquarters of the Protectorate from devastated Tulagi to a new site between the Mataniko River and Point Cruz. The Americans valued the pre-made town at US$10,359,695. (Bathgate 1977, 5) No one thought about asking permission from the people of the area; after all, the land had been alienated for more than half a century. And no one thought to ask other Solomon Islanders if they would like a new capital perched on a narrow coastal plain backed by dry coral rock ridges, all very sunny, exposed and infertile.

1940-1950s

In December 1947, Qantas Empire Airways surveyed a possible new route from Australia via New Britain, Guadalcanal and Nauru, extending its 'Bird of Paradise' service. Qantas began regular charter services in June 1949, including the monthly Catalina flying boats of Trans Oceanic Airways, which operated out of Sydney to New Caledonia, New Hebrides and Tulagi. Some flights flew from Sydney to Honiara via Papua New Guinea, then on to Barakoma (a wartime airstrip on Vella Lavella) and the private Levers Pacific Plantations airstrip at Yandina, Russell Islands. Trans-Australia Airways (TAA) and Fiji Airways began services in 1952 using the same route, at first landing at Honiara's Kukum Fighter II airfield and later at Henderson Airfield, after it was upgraded. These airlines used DC3s, Fokker Friendships and Heron aircraft. Alan Lindley, who arrived in Honiara in 1952, remembers one rather bizarre detail. There was no radio communication at Kukum or Henderson airfields before 1958, so the local radio station used to play 'Slowcoach' by Pee Wee King and his Golden West Cowboys on its frequency to enable the planes to home in using their radio directional loop. (PIM Dec. 1947, June 1948, May 1952; AR 1949-1950, 5, AR 1953-1954, 41; Tedder 2008, 15; Alan Lindley, personal communication, 30 June 2011)

In 1945, once the decision was made to shift the capital to Honiara, a town plan was prepared by Mr Bentovsky and a quarter-million pounds was requested from the High Commissioner, only one-fifth of which was allocated. (NS 31 May 1969) It took until after 1953, when the High Commission was moved to Honiara, for extra attention to be given to shaping its development. More housing was built for the growing number of public servants, and government buildings were improved or replaced.

The Americans left behind a rudimentary road system, although there were no permanent bridges over most of the rivers. In early 1948, six Bailey bridges were imported at a cost of £24,000 to replace dilapidated timber bridges on Guadalcanal. (AR 1953-1954, 8; PIM Jan. 1947, Feb. 1949, Dec. 1949, Mar. 1951, Feb. 1952; Michener 1957 [1951])

The first Bailey bridge erected was the present-day Chinatown bridge over the Mataniko River that was completed in June 1950. The initial labour supply for building British Honiara came from rotated batches of sixty Fijian and Indian workers from Suva, housed in the area still known as the Fiji Quarter (q.v.) near Chinatown. In 1948-1949, Honiara's population consisted of about eighty Europeans, including twenty-three women and eighteen children, one hundred Chinese living in what is now Chinatown, the workers in the Fijian Quarter, and Solomon Island labourers. Up until 1948 there had been a severe labour shortage in Honiara because of an informal strike by the Maasina Rule movement (q.v.), but the supply improved in 1949 and was adequate by 1950. By 1949, Honiara was fully surveyed, twenty-four new houses had been built for European residents, and 'labour lines' (barracks) had been constructed at Kukum. (The latter were extended in the early 1960s.) The supply of ivory palm leaves was insufficient and often the government had to fall back on timber and iron for house-building materials, and it relied extensively on second-hand American buildings and materials. (AR 1949-1950, 26)

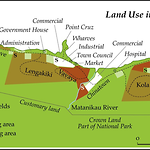

The population rose quickly and reached 2,500 in the mid-1950s, and by 1959 Honiara was home to 3,534 out of a total Protectorate population of 124,000. By 1966, Honiara had fifty-five registered shops and stores, nine tailors and three bakers. A substantial Chinatown developed on the eastern bank of the Mataniko River, containing a non-residential hotel (really just a fairly rough bar) and thirty-nine of the registered businesses in Honiara. Most Solomon Islanders shopped there. (NS 7 Apr. 1966; Nage 1987) The government administrative centre was concentrated around Point Cruz. Premises varied from modified Quonset huts to modern air-conditioned banks and supermarket buildings. Four businesses were registered at White River, two at Kukum and three at Kola'a Ridge. Urban associations began to form, more hotels were built and roads were given names. A Jaycees branch, a Masonic Lodge and a Chamber of Commerce were established. (NS 19 Dec. 1966, 31 Jan. 1969; SND 3 June 1977) A multi-racial Solomon Islands Club, later named the Honiara Club (q.v.), was begun in July 1964 in one of the Quonset buildings near the Central District Office on Mendana Avenue as temporary premises. Many Europeans felt more comfortable at the more exclusive Golf Club that opened in 1957, with its local-style sago leaf clubhouse. In 1959, plans were unveiled to extend the course to nine holes, and a permanent clubhouse was built in 1964. Expatriates also congregated at the Guadalcanal Club and at the Point Cruz Yacht Club.

The more literate appreciated the opening of Honiara Public Library in mid-1968, which had space for twelve thousand books. That number had almost been reached by 1970, when the library had ten thousand volumes and 782 expatriate and 403 indigenous borrowers. (NS 13 Dec. 1967, 31 Aug. 1968, 30 Nov. 1968, 28 Feb. 1970) A few of the more musical residents joined 'Honiara Deadbeats', the 'hottest jazz band in two million square miles of the Pacific', which performed in local repertory events. Others joined the Chess Club or the Film Society. The main public celebration was the Queen's Birthday in June, when a parade was held and many decorations and awards were presented, followed by a garden party and ball at Government House. (Gutch 1987, 115-116; NS June 1966, 31 Jan. 1968, 16 Oct. 1972)

Chinatown

Honiara's Chinatown of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s was the classic two-sided street of wooden red, green and blue trade stores with tin roofs, and crossed-frame railing around the front verandahs. The business was conducted behind counters in the central rooms and there were living quarters at the back. The same style of Chinatown existed at Gizo and Auki, with business links to the Honiara shops. Chinese business houses also began to extend into major business operations. The largest was Quan Hong Pty. Ltd. (q.v.), which opened a substantial bêche-de-mer processing factory at Kukum, and its famous Joy Biscuit factory. They were also increasing numbers of Chinese importers and exporters, plantation owners, ship owners and general merchants. (NS 31 Mar. 1967, 7 June 1967)

The children of the first generation of Chinese were blocked from taking expatriate-salaried government jobs; although many were Australian-educated, they were domiciled in the Solomon Islands and ineligible for the overseas salary supplement. The younger Chinese left the family trade stores and branched out into other commercial ventures. They supplied logging camps, marketed trochus shell and bêche-de-mer, and began specialist shops in the central business district along Mendana Avenue. There were always tensions because Solomon Islanders resented the Chinese stranglehold on retail and wholesale business, but the Chinese worked hard and served the nation and themselves reasonably well. They prospered under the later decades of the British administration, which operated in a fairly non-corrupt and straightforward manner. During the years around independence the Chinese were uncertain about their future welcome, but many families stuck it out and have prospered since. They have become leading hoteliers, owners of a wide range of businesses, and even parliamentarians. (PIM June 1950; NS Oct. 1961, Feb. 1962, 15 Nov. 1965; Moore 2008c)

Some Chinese men married Solomon Islander women a generation ago, which has stood them in good stead in periods of conflict in Honiara during which local connections have been crucial. Families such as the Chans have entered the mainstream as hoteliers and latterly as politicians. A few other Asians prospered as well, such as Japanese businessman Yukio Sato, who established himself in Western District in the 1950s before shifting his business interests to Honiara.

Solomon Islanders and Honiara

The 1959 Census spelled out something that had been clear since Honiara began, and worried authorities. Although males and females were well balanced in the overall Protectorate population, in Honiara single males made up 40 percent of the indigenous population and 25 percent of the total population. The majority came from Malaita, a harbinger of the problems to come in the 1990s. While Malaitans dominated overall and were the main labour force in Honiara, all islands were represented in the new urban centre. For instance, Choiseulese, rather like the Malaitans, came to Honiara to find work and pursue lifestyles impossible on their own island. (Kengava 1979) The main drive was to find employment in the new town and to better their economic and social circumstances. Later the momentum was increased by wantoks migrating to join existing families or individuals, just as occurs today. However, wages were low and there was insufficient accommodation available for families, and much of the unskilled labour force was transitory. In 1958, 40 percent of the labourers worked in Honiara for three months or less, 20 percent for three to seven months, and 15 percent for six to twelve months. (Tedder 1966, 37) However, by 1960, building contractors, other employers and the Public Works Department were able to engage all necessary labour in Honiara, and only the Ports Authority still recruited stevedores from elsewhere for its Honiara-based activities. (AR 1959-1960, 8) The first meeting of the Legislative Council (q.v.) in 1961 discussed the problems created by Solomon Islanders who were visiting Honiara without sufficient means of support and thereby causing financial hardship for permanent residents. The administration was asked to report on possible remedies. (Legislative Council Debates, 2 May 1962, 48)

Initially, Solomon Islanders from outside Guadalcanal saw Honiara as a place to earn money quickly and return home. Home remained their islands of origin, and most families returned there on annual holidays. The Guadalcanal population had long been displaced from the Honiara area and was not large. In this way Honiara differed from Papua New Guinea's Rabaul, Lae and Port Moresby, where nearby villagers supplied much of the manual labour and were employed to do lower-level clerical work. As children began to be born in Honiara they still identified with their parent's islands of origin. Over decades, there has been a shift as many Honiara-born residents have now lost touch with their ancestral roots, seldom if ever return to their parent's villages and neglect cultural obligations. One index of this has always been the place of burial for any Solomon Islander who dies in Honiara. The old pattern was for almost all to be buried back on their ancestral lands, but as decades pass there are an increasing number of burials in Honiara as the city becomes a permanent home for many families. (Frazer 1985; Friesen 1986)

1960s: Infrastructure

In the late 1950s, Honiara had a population of around 3,550 people, and by 1965 6,684 people. In 1968, the estimated population was eight thousand, which grew by a thousand in 1969, a 12.5 percent increase. (NS 28 Feb. 1970) In the 1970 census the population was 11,191 persons: 7,237 males and 3,954 females. The proportions of Solomon Islanders had changed considerably. Between 1959 and 1965 males had increased from 2,297 to 3,980, up 73.2 percent. Women had increased in numbers from only 520 in 1959 to 1,426 in 1965, an increase of 174.2 percent, creating a more balanced, if still imbalanced community. The size of the European population had more than doubled over the same years, from 363 in 1959 to 624 in 1965. The number of Chinese had risen from 266 to 414, an increase of 64 percent. These increases, particularly the greater number of indigenous women in Honiara, meant that housing and services had had to increase fast. (AR 1965, 5, AR 1969, 90, AR 1971, 7; Tedder 1966)

The remnants of the American wartime camps gradually disappeared, replaced by new buildings and facilities. One large stimulus to Honiara was the new national educational institutions located there. However, all of this infrastructure development meant that Honiara absorbed a large proportion of Protectorate and WPHC expenditures. By the 1960s, Honiara absorbed about two-thirds of the Protectorate's capital expenditure on utilities, buildings and communication. Several severe problems were difficult to solve. One was that, because Honiara was located on a former battleground, there was wreckage along the shores and hundreds of unexploded bullets and bombs almost everywhere. In the first few years of the British Solomon Islands Training College at Kukum more than four hundred shells were uncovered on the grounds and had to be destroyed, and the same was true all around Honiara. The largest bomb found, a 500 pound device thought to be Japanese, was detonated at Henderson airfield in 1968. (NS 14 Feb. 1968) Later that same year a man was killed when a bomb exploded in a fire at Kukum, and in 1970, 75 millimetre shells, two mortar bombs and three hand grenades were found in a valley at Kola'a Ridge. (NS 15 May 1968, 15 Sept. 1970)

Another continuing problem, which remains Honiara's biggest weakness today, was the water supply. Honiara's original supply was provided by a combination of rainwater tanks, and boreholes at Kukum. Electric pumps were submerged in two boreholes, supplemented by six permanent springs caught in a small dam. (NS 31 Jan. 1969; AR 1949-1950) From 1965, the Mataniko River water was used, stored in a series of large tanks in different locations. Water pressure has always been poor in hill areas like Skyline and Kola'a Ridge, and also on the other ridges as new houses were built. For sixty years, Honiara's residents have complained about rationed and inadequate water supplies, and there is little solution in sight and larger problems looming as Honiara continues to grow. More boreholes have been sunk over the years but there seems to be no prospect of there ever being a large dam to supply water to Honiara.

Another problem with the Honiara location, which has now been rectified, was the lack of a port. During the American occupation in the 1940s the main wharf was at Kukum, with a smaller temporary wharf at Point Cruz. Kukum docks had three sections, two at right angles to the shore and one parallel, forming three sides of a rectangle. The Kukum facility was used as the main wharf for overseas shipping, but the most easterly section fell into disrepair and was demolished, and the other sections were destroyed in a cyclone in January 1952. After this, ships had to load and unload at Tulagi. The first stage of building new port facilities for Honiara was approved in September 1955, and the new deepwater berth was used for the first time on 15 February 1966. This also enabled cruise ships to visit, the first being Orcades in August 1967, which provided a market for artefact sales. (PIM Mar. 1951; NS 1 Sept. 1955, 12 Sept. 1955, July 1960, 15 Feb. 1963, 31 Mar. 1964, 14 Feb. 1965, 21 Feb. 1966)

Honiara's public and commercial facilities began to become permanent and more substantial during the 1960s. Honiara Town Council's new fish market, with its freezer, cold store and ice-making facilities, opened in May 1966, leased to the Honiara Co-operative Fish Marketing Association Ltd. Guadalcanal Bus Service began in 1968, travelling from King George VI School (q.v.) to White River, operated by partners Monty Ho, William Chan, James Kwan and Nga Kwak Kwan, with William Chan as General Manager. A second bus was added in 1969 and a third in 1970. (NS 31 Aug. 1968, 15 May 1969, 31 Dec. 1969; SND 6 Feb. 1975) The red busses trundled back and forth until the introduction of the smaller buses of today made them obsolete. A permanent wharf was constructed next to the fish market in 1969, which allowed small ships and canoes to bring produce directly to the market. (NS 15 Apr. 1969) The Australian and New Zealand Bank (ANZ) opened its first branch in Honiara in mid-1966. (NS 7 May 1966)

In 1969, Honiara held the first National Agricultural and Produce Show, the forerunner of many similar events to come. Substantial churches and cathedrals were also built and remain the focal points of life for many Solomon Islanders. In European tradition, the presence of cathedrals is taken as the marker of the difference between a town and a city. In Honiara, the foundation stone for Anglican St. Barnabas' Cathedral (q.v.) was laid in 1961, and the completed building consecrated in 1969, while the Catholic's Holy Cross Cathedral was finished during 1977-1978. Both cathedrals replaced earlier temporary structures. (NS 31 July 1957, June 1960, Feb. 1961, 7 July 1967, 30 Nov. 1969; AR 1968, 82, AR 1969, 80-81; SND 18 Mar. 1977) Even if, by dint of its cathedrals, Honiara was a city, it was still a small colonial town replete with racial attitudes that segregated indigenous and non-indigenous inhabitants.

Sporting facilities, crucial in any city, developed in Honiara. The sports grounds (q.v.) and playing fields became known as 'tama', which means 'park' or 'ground'. Sports (q.v.) became a central part of the lives of Solomon Islanders and large crowds attended Sunday afternoon football matches. (Bellam 1970; Bathgate 1977)

1960s: An Education Hub for the Pacific

A small Protectorate Education Department was established in Honiara in 1946, with just three positions, which functioned under considerable difficulties. The first Director, C. A. Colman-Porter, resigned in 1948, leaving an Inspector of Mission Schools as the only person in the Department during 1949, and she departed in 1950. The missions still conducted all education in the Protectorate, except for a part-time school in Honiara for European children, and the Chung Wah School (q.v.) for Chinese children, which opened in October 1949. The expatriate students of Honiara's Woodford School (q.v.) were enrolled in the New Zealand Correspondence School. (AR 1953-1954, 26)

The postwar BSIP government initiatives flowed on from the appointment of Colman-Porter and a November 1947 conference for all educators. The conference outlined a new policy to create state institutions to provide skills for the Protectorate in teaching, nursing, agriculture, commerce, carpentry and engineering. The only concession to the Christian missions was a rather strange plan to allow colleges within these institutions to be organised according to religious denominations. This development was delayed after Coleman-Porter resigned in 1948, after he realised that he did not have the support of the government. A new conference held in March 1949 was no more conciliatory to the churches than the 1947 conference had been. New BSIP education regulations were circulated in 1953, stipulating new multi-course colleges to produce practitioners in all of the skills needed to develop the Protectorate. (Laracy 1976, 151-152) This was the foundation of what eventually became the Teacher and Vocational Training College, the British Solomon Islands Training College, the Agricultural Staff Training Institute, Central Hospital in Dressers School, the Nurses' Training Centre, Auki Boatbuilding School, the T.S. Ranadi Marine Training School, and finally the Solomon Islands College of Higher Education. All of these institutions brought a new generation of young Solomon Islanders to Honiara, along with a mix of fellow students from the Gilbert and Ellice Colony (Kiribati and Tuvalu), the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) and a few other Pacific colonies. Honiara slowly became more cosmopolitan and better known throughout the Pacific, a change aided by the removal of the Western Pacific High Commission headquarters from Suva to Honiara in January 1953.

Urbanization

During the late 1970s and 1980s, Honiara's urban sprawl began to move inland through the rolling valleys back from the beach. The government continued to develop housing estates: in 1967, 112 houses were built at Vura Creek and sixty at Rove, mainly for police families, and a hostel for single girls was planned. (NS 7 June 1967) The first stage of what is now the large suburb of Vura began with the multi-stage Vura Housing Estate, with a plan to construct three hundred family homes, a primary school and a retail area. The smallest houses, with two bedrooms, a veranda, kitchen, septic toilet and a shower, cost over A£1,000, at a time when junior clerks and artisans earned around A£200 a year. Rents varied with salaries, but were capped at an uneconomical A£12 per year, which did little to encourage people to buy or build their own houses. (Tedder 1966, 37-38) The Housing Authority was formed in 1970 and enabled Solomon Islanders to obtain small loans to purchase houses. More houses were constructed at Mbokonavera, Kola'a Ridge, Koloale and at Mbua Valley (Kukum), and new housing estates developed at Tuvaruhu, Vara Creek. (AR 1971, 4, AR 1974, 81-82; NS 15 Mar. 1970; SND 4 Apr. 1975)

Communal urban facilities slowly increased in number. The Christian churches led the way in providing facilities such as multi-purpose church buildings and halls adjoining churches. A Solomon Islands Community Centre, constructed in 1971 between Chinatown and Lawson Tama sports ground, close to the new urban sprawl areas, provided a multi-purpose indoor sports and meeting place. A swimming pool was added in 1973, but it closed in 1975 due to the high costs of operation. (AR 1971, 5; NS 7 May 1973)

Honiara's boundaries were increased in 1969, expanding the town from 3,800 to 4,800 acres, although at the time this only added one hundred people to the population. The boundaries were extended inland to include the new government housing estate at Tavaruhu on the Mataniko River, and the areas to the south to Kola'a Ridge, including squatter settlements. This brought into the city boundaries the planned 3,705 hectare Queen Elizabeth National Park (q.v.) south of Honiara. (NS 15 Feb. 1969; AR 1953-1954, 31) Also in 1969, the Honiara Council took over education activities and opened its first new school on the Tavaruhu Housing Estate. The Council effectively took over responsibility for all new schools except for church schools. The next school was opened at White River, and there were plans to open schools at Vura and Mbokonavera. (NS 28 Feb. 1969)

There were whole areas of housing where foreigners never visited, some of them formal suburbs and others squatter areas. Squatting became a considerable problem as more people migrated to Honiara, attracted by employment opportunities. The accommodation provided by employers was often inadequate or non-existent and people also needed garden land so as to be able to supplement their meagre wages. They began to build houses in squatter settlements from bush materials or a combination of bush materials and scavenged or purchased materials. A good example of the problem was people who occupied single labour quarters and then brought their families to join them. They usually had a small wage and could not afford to rent houses, even if they were available, and so they moved to squatter settlements such as Matariu. Sanitation in these settlements was poor and they had no reticulated water supplies, and so people depended on streams and tapping into other local supplies. The squatters, and even many among the emerging Solomon Islander middle class, also worked in gardens on weekends, usually on government land. The area designated as Queen Elizabeth II National Park around Mt. Austen was highly vulnerable to this and soon most of it had been cleared for gardens. Eventually, the Honiara Town Council established a system of Temporary Occupation Leases.

Political Processes

As preparation was made to hand over political power to Solomon Islanders, Honiara became central to the process. Through a series of constitutional changes (see Constitutions), Solomon Islanders served on the Advisory Council (1951-1960), the Executive Council (1960-1969), the Legislative Council (1960-1969), the Governing Council (1970-1974) and the Legislative Assembly (1974-1978) (all q.v.). The first general election (see Elections) was held in all eight constituencies on 7 April 1965. The member representing Honiara constituency was elected by direct ballot, while the other seven were chosen by an electoral college, its members chosen by the members of the Local Councils. The first direct election occurred in May 1967. Sixty-two candidates contested fourteen seats, and 17,689 votes were cast (of 35,101 registered voters, a turnout of 50.3 percent). The Honiara seat was contested by Bartholomew Buchanan, a senior executive officer in the government, William Ramsay, Manager of the BSIP Ports Authority, and Lilly Ogatina Poznanski (q.v.), the sitting member for the former electoral district of Central Solomons excluding Guadalcanal. Ramsay received 211 votes, Buchanan 157 and Poznanski 20. (NS 21 May 1967) The first political party (q.v.) was formed in 1965.

This new political process added special complexity to Honiara, particularly through the direct elections and the early political parties. Political parties were never strong and lacked ideological bases, except for those connected with trade unions. Early campaigning was lacklustre compared with the extravagant affairs of today. Until a national parliament house was constructed in the 1990s, the meeting place was the Teachers' College, and later the Supreme Court building. Politicians, unless they were in charge of departments, had no offices and met constituents in their rooms at the Parliamentary Resthouse in Hibiscus Avenue, at their homes if they were Honiara-based, or wherever they were living with their wantoks. Telephones were mainly confined to government offices and not found in private homes, although eventually most middle-class homes installed them. Constituents found that it was best to call on Members of Parliament at home, early in the morning or in the evening. As still occurs today, a great deal of business was conducted while walking along Mendana Avenue or while shopping at the Central Market, Chinatown or the variety of stores in Point Cruz. The Mendana Hotel and the Yacht Club also became favourite gathering places. Church buildings were also integral to the political process, since almost all Solomon Islanders attended church one or more times a week.

Honiara had become a major Melanesian city, along with Port Moresby, Lae, Suva, Noumea and Port Vila. By the time of independence, Honiara was a bustling, thriving city based on an inherited American infrastructure, and designed by the British according to their own colonial precedents, but inhabited by Solomon Islanders who were slowly changing it to accommodate the needs of wantokism (q.v.), lius (q.v.), extended families, work, travel to and from other islands, access to gardens, daily trips to the market and weekly visits to church.

Related entries

Published resources

Books

- Clemens, Martin, Alone on Guadalcanal: A Coastwatcher's Story, Originally published: 1998, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2004. Details

- Golden, Graeme A., The Early European Settlers of the Solomon Islands, Graeme A. Golden, Melbourne, 1993. Details

- Gutch, John, Colonial Servant, T.J. Press, Padstow, Cornwall, 1987. Details

- Laracy, Hugh M., Marists and Melanesians: A History of the Catholic Missions in the Solomon Islands, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1976. Details

- Michener, James, Return to Paradise, 1957 edn, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1951. Details

- Tedder, James L.O., Solomon Islands Years: A District Administrator in the Islands, 1952-1974, Tuatu Studies, Stuarts Point, NSW, 2008. Details

Book Sections

- Kengava, Clement, 'Choiseul Immigrants in Honiara', in Peter Larmour (ed.), Land in Solomon Islands, Institute of Pacific Studies and Solomon Islands Ministry of Agriculture and Lands, Suva, 1979, pp. 155-166. Details

- Moore, Clive, 'No More Walkabout Long Chinatown: Asian Involvement in the Solomon Islands Economic and Political Processes', in Sinclair Dinnen;Stewart Firth (ed.), Politics and State Building in Solomon Islands, Asia Pacific Press, Canberra, 2008c, pp. 64-95. Details

- Nage, James, 'Immigrant Settlements in Honiara, Solomon Islands', in Leonard Mason;Pat Hereniko (ed.), In Search of a Home, Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, Suva, 1987, pp. 93-102. Details

Conference Proceedings

- Bathgate, Murray A. (ed.), The Honiara Market in the Solomon Islands. A Study of the Supply of Food from the Rural Area and the Marketing Behaviour of the Vendors, Food, Shelter and Transport in the Third World Seminar, Australian National University, Canberra, 1977, 103 pp. Details

Edited Books

- Laracy, Hugh M. (ed.), Pacific Protest: The Maasina Rule Movement, Solomon Islands, 1944-1952, Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, Suva, 1983. Details

Journals

- Pacific Islands Monthly. Details

- Solomons News Drum, 1974-1982. Details

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate (ed.), British Solomon Islands Protectorate News Sheet (NS), 1955-1975. Details

Journal Articles

- Bellam, M.E.P., 'The Colonial City: Honiara, a Pacific Islands 'case study'', Pacific Viewpoint, vol. 11, no. 1, 1970, pp. 66-96. Details

- Frazer, Ian L., 'Walkabout and Urban Movement: A Melanesian Case Study', Pacific Viewpoint, vol. 26, no. 1, 1985, pp. 185-205. Details

- Tedder, James L.O., 'Honiara (Capital of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate)', South Pacific Bulletin, vol. 16, no. 1, 1966, pp. 36-41 (43). Details

Reports

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate, British Solomon Islands Protectorate Annual Reports (AR), 1896-1973. Details

Theses

- Friesen, Ward W., 'Labour Mobility and Economic Transformation in Solomon Islands: Lusim Choiseul, Bae Kam Baek Moa?', PhD, University of Auckland, 1986. Details

Images

- Title

- Honiara in the mid-1950s, looking towards the then three shops in Mendana Avenue

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1950s

- Source

- Alan Lindley

- Title

- Mataniko River and the outskirts of Chinatown from Skyline Road, Honiara

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1950s

- Source

- Alan Lindley

.png)

- Title

- Mendana Avenue and its red-flowering Poinciana trees, Honiara

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1950s

- Source

- Patrick Barrett

- Title

- Mendana Avenue, Honiara, and its red-flowering Poinciana trees, looing towards Central Police Station

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1961

- Source

- Patrick Barrett

- Title

- Point Cruz, Honiara in the 1920s, looking from the Kukum area

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1920s

- Source

- Raucaz 1928

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)